If this trend continues, the steady supply of Pentagon dollars might eventually help a company like Vigor become big enough to challenge military contracting giants on larger, more lucrative projects, such as actually building warships. And then just last month, Vigor was one of three firms named to compete for work under a $671 million umbrella contract to maintain surface warships visiting Naval Station Pearl Harbor.

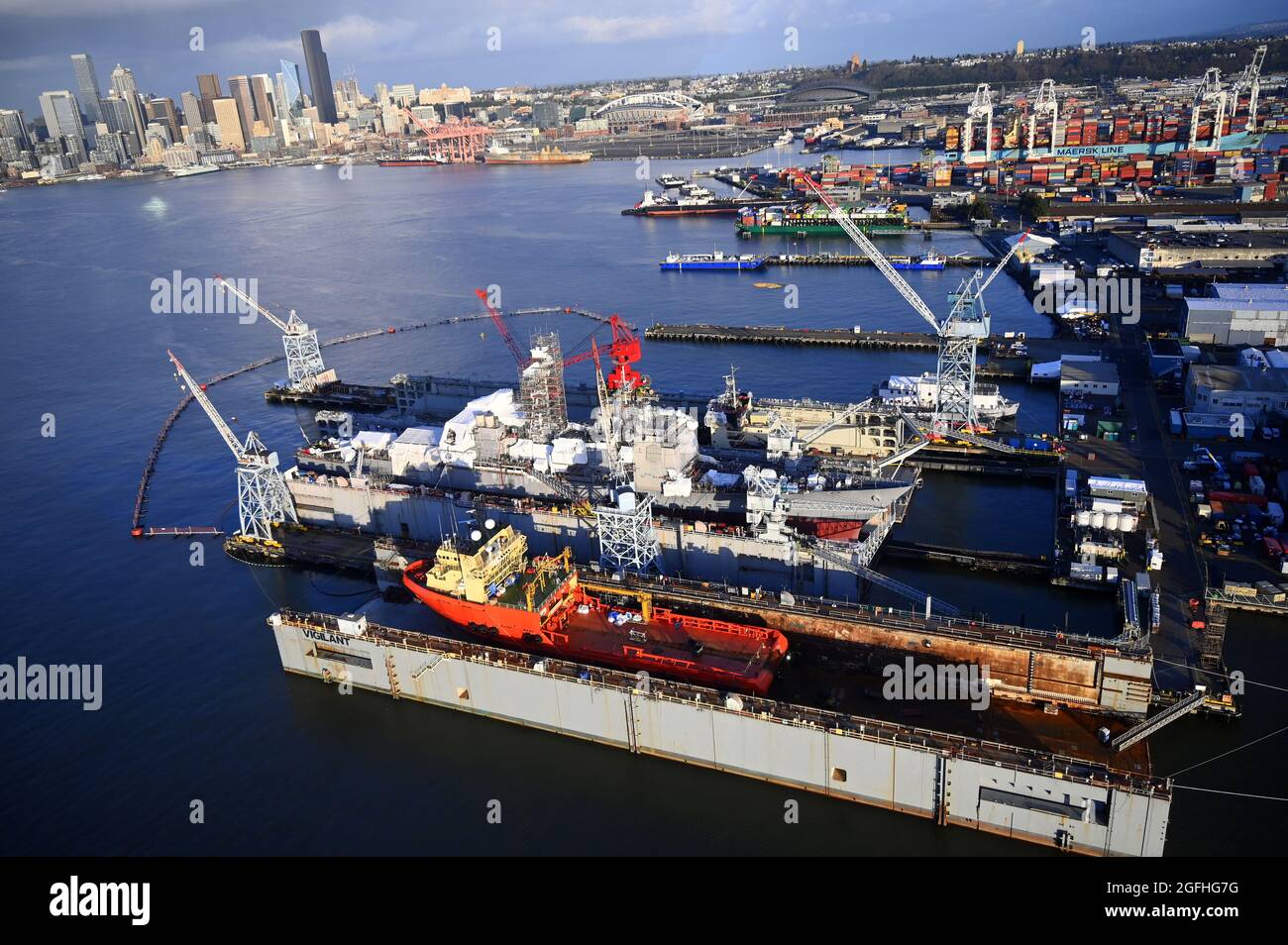

#Vigor shipyard upgrade

But last September, for example, the Navy awarded Vigor $255 million to repair and upgrade two Ticonderoga-class guided missile cruisers. Most of these contracts were admittedly small, on the order of a few million dollars. Moreover, fewer companies competing on price can defeat any gains reaped by greater efficiency of production. On the other hand, big companies aren't always as nimble or as innovative as smaller companies. Bigger companies have greater economies of scale to keep costs low, and more financial heft to withstand downturns in the economy. Maybe this isn't necessarily a bad thing. Count small-fry drone makers such as Kratos and AeroVironment, and you're maybe back up to 11 - but still a long way from 50. Throw in truck builders Oshkosh and Textron and electronics specialist 元Harris, and that gets you up to nine companies.

Since the end of the Cold War 30 years ago, a series of mergers, reorganizations, and bankruptcies has shrunk the roster of big, independently operating defense companies from more than 50 to just a handful: Lockheed Martin, Boeing, and Northrop Grumman, focusing mainly on aerospace and General Dynamics, Raytheon, and Huntington Ingalls ( HII -1.47%), handling ordnance, electronics, armored vehicles, and warships. But it's not so much the amount of total defense spending that's shrinking, but rather the number of companies divvying up the loot. America's military-industrial complex is shrinking. To some (defense policy doves), that may sound like good news.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)